People Power and Housing – Centre, Left, and Right.

The protests that washed across major cities and towns a few days ago, covered a wide variety of issues, yet underlying them all is dissatisfaction with both sides of politics and the frustration in the community that ‘voices’ are going unheard.

We’ve been used to seeing similar demonstrations across the austerity-ridden countries of Europe and the USA, and political clashes such as those in Russia and most recently Ukraine

Yet since the fall out of the last economic crisis, a concentrated outcry of public anger has penetrated democratic society and it’s not limited by ‘cause’ or segregated by age and status, but generated by the incredible impact of social media enabling a wide array of ordinary citizens to vent their concerns outside of sporadic government polls and the headline sensationalism of main stream media.

The natural limitation of Government is the inability to please all, and no one would expect as such. In a democratic society, they’re elected to enact on the policies campaigned upon – asked to lead rather than follow and ensure citizens achieve a platform that assists in advancing equitable outcomes.

Albeit, it’s a brave Government that turns its head away from large vocal demonstrations, especially in an age where – through the connectedness of social media – they can be arranged at the drop of the hat, bypassing the usual bureaucratic process of writing to a local MP to highlight community disquiets, or publishing a letter in the local paper.

You can argue back and forth about the issues surrounding this latest public protest. Express outrage at the inconvenience incurred to the daily commute. Or even question its relevance considering we have not long elected the Coalition into power. But when a wide makeup of individuals, from all sides of the political spectrum, takes to the streets – not on one agenda alone – but an array of disgruntlements. It is no longer merely representative of a minority that sits on the fringes of society; it signifies a clear message of distrust – a potentially destabilising force.

“Cone of Silence”

Tony Abbot’s government made it clear upon election, that they intended to control the flow of information available for public discussion.

It wasn’t only displayed in the media restriction detailing daily boat arrivals, but in a large array of research undertaken by the previous administration, which has now been firmly locked into ‘archive’ status.

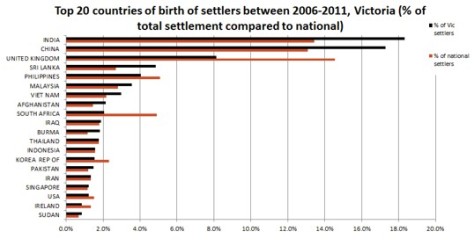

This would include two I’ve mentioned in recent columns – the National Housing Supply Council, and the year long study that formed the white paper into the “Asian Century,” which outside of general criticism, remains a useful tool of reference for Australia’s future demographic makeup.

So you could say that listening to the public voice, isn’t the current Government’s priority – but then, neither was it for the last.

Little if anything came from those reports. The were good on content, but lacking in action – and much like the “2020” summit in 2008, the results can be summed up neatly by words from biographer, Nicholas Stuart, in ‘Rudd’s Way – November 2007 – June 2010;’

“….His rhetoric inspired and enthused voters. And yet …. and yet …. nothing happened.”

“Nothing happened” – because Governments too often bend the knee to those with the ability to influence political leadership and public opinion, rather than acting ‘democratically’ for all.

Housing policy alone aptly demonstrates this.

- The tax and transfer system values owners over renters;

- Encourages and rewards those who use the land as a speculative investment for personal gain;

- Advantages giant corporations over independent businesses;

- Widens the ‘wealth’ gap between rich and poor;

- And hampers timely development of affordable housing; (to name only a few.)

When concerns are raised, our leaders spend a few wasted millions on comprehensive enquiries to ask ‘why?’- like some clueless high school student.

“What do we want?..”

These protests, whilst not directly about land prices, were about community and social justice, of which housing forms an indivisible part.

The list includes education – and as I’ve pointed out previously, high land prices directly contribute to what’s assessed to be the most segregated schooling system out of all members of the OECD countries.

Some of the highest land values are found in the best Government funded school catchment bands, and as an auctioneer proclaimed during his pre-amble in the McKinnon High School zone last week;

“There is no ceiling for house prices in this area.!.” A bullish spruik if ever you heard one – but not far from truth.

Record prices continue to be regularly broken, affluent buyers continue to pay a premium. Yet the price is effectively ‘free,’ because as the zone’s future vendor’s ‘speculate’ – if they hold onto the family home long enough – they are likely to receive a ‘windfall’ in unearned capital gains.

Social Justice? Hardly.

Unwonted robbery?

The community produces the gains through the tax-funded facilities. Whilst market forces drive prices higher, the unearned profit does not flow back to maintaining or upgrading those services – which is where it arguably belongs.

Instead it is privately capitalised– soaked into what is an irreplaceable, illiquid

and unproductive asset, thereby giving free leave for mounting property prices to continue, which, under the current system, grants a ‘tax free’ unearned reward to the owner occupier upon sale

The sell off of public services was also highlighted. This too can also be associated with high land values, which have dictated what is assessed to be the more profitable offloading of the Millers Point public housing estate, rather than retaining its use for long standing residents, which, by definition, drives social polarization and housing inequality.

It seems in the land of a ‘fair go,’ only the affluent are allowed to advantage from a Sydney Harbor view.

Are They Listening?

Yet the indicators Government use to measure their performance whilst in power are meaningless to protesters, and in many respects, a 21st century economy.

They are no measure of happiness, or signal the worrying rise of mental illnesses such as depression.

Only by ‘hearing’ community voices, gives a clue to that.

GDP – the total value of all products and services bought and sold, a basic measure of money changing hands, does not distinguish between;

- Productive or destructive activities,

- Show who’s getting the lion’s share of wage increases, Or

- Assess where those increases are being invested; (Which, considering housing (land) is currently estimated to be 300% of Australia’s GDP, gives some indication.)

Equally it gives no clue to the foundations of societal health – such as environmental concerns, access to education, or wealth inequality.

Yet these are the issues community wants to address – because these are the barometers that directly impact our quality of living.

Whilst GDP is an excellent measure of the amount of arguably unneeded ‘stuff’ changing hands, it’s also not up to the task of adequately measuring intellectual property, innovation and invention for example – such as the creation of a free app.

It may be concerned with the health of the economy, but as for the well-being of our 21st century community – it’s simply not up to the task.

Equally, unemployment figures are based on theoretical estimates, formulated by way of an extensive ABS survey, which aims to correlate the percentage of the labor force not actively employed, underemployed, or ‘participating.’

They are rolled out monthly, with the widely held ‘text book’ assumption (known as NAIRU) that, regardless of how many actually want to work, should Government pro actively attempt to lower the rate of unemployment below the desired level of “full employment” – which in Australia, is assessed to be and ‘unemployment rate’ of roughly 5% – it would unwontedly induce inflation and destroy price stability.

A purported ‘fact’ that offers no comfort to those living on the poverty line of job seekers allowance.

This is also largely due to our flawed system of taxation – which places a levy on productivity, (such as income and payroll taxes,) unwontedly impeding the supply of goods and services, which in turn raises prices, feeding inflation and increasing the unemployment rate arguably ‘required’ to lower wages sufficiently to stabilize inflation

If we instead moved toward a system – and one, which was, at least in part, advocated by the Henry Tax review, and not withstanding, numerous other submissions from community advocates such as Prosper Australia, or the Land Values Research Group to various senate enquiries over the years. And taxed the unearned gains from land (as mentioned above,) rather than the earned gains from productivity.

It would (as has been proven historically) influence;

- A reduction of social polarization – and therefore inequality.

- Remove the needed ‘sell off’ of public services due to high land values.

- Boost productive investment, assisting the job market and advancing competitiveness for small business.

- Reduce the speculative element that drives land prices ever higher.

- Provide a steady base of revenue to invest in public services as well as affordable housing, and;

- Ensure infrastructure is built for need – full utilization of land encouraged – and land banking reduced.

Productivity Paradox

In light of all the above – it is remarkable that back in the 60’s and 70’s, discussion in the university lecture halls was centred on the ‘productivity paradox’ – correctly assuming it only a matter of time before all mankind’s basic needs could be largely fulfilled by robots (which they has been.)

Economists were deliberating what we’d do with all our leisure time when a full working week was no longer necessary!

A stark change from the current mode of discussion, which is consumed with how long past the age of 65, individuals will need to work in order to retire mortgage free, with enough left in the pot to afford the basic necessities of life, which in most cases, is inadequately funded by super annulation alone.

If it were possible to send the dog to work, we’d have already done so.

Community

Indeed our economy is not founded on the pillars of community and social justice, of which the protests are so concerned.

As admirable as numerous recommendations made to various senate enquiries into issues of inequality, affordability, finance, and environmental concerns have been, nothing has changed, because we have a lopsided economy, built on a $5.02 Trillion housing market ($4.1 Trillion of which is land) – and on this, and many other matters alone, a new generation of enlightened folk have clearly had enough.

High land values have played an important part in all the issues of social inequality highlighted above, of which I’ve provided ample evidence in previous columns.

Our major cities now exhibit what’s considered to be a very ‘non Australian’ style ‘English’ cultural class divide – as polarization between the asset rich and income poor expands.

The roll on effect impacts the environment, employment, education, and mental illness – as residents are forced into areas lacking in essential amenities – once again due to a flawed system of finance and housing policy.

To Conclude..

And so, when you start to see what is so beautifully highlighted using the maps below, which show where the affordable property was located in 2001 for low and middle income buyers, compared to 2011 in our major capitals, which hold the lion’s share of population.

(The yellow patches being affordable, and blue patches unaffordable.)

And you read quotes from a long standing resident advocates, at the soon to be forced out Millers Point public housing facility, who rightly question;

“The government says their core business is not housing. But surely their core business must be communities….?!”

Then you start to get a grip on the central issues this protests represents;

And I would suggest – (as expressed on their website) – it really is “only the beginning.”

Catherine Cashmore

By Catherine Cashmore, a market analyst, journalist, and policy thinker, with extensive industry experience in all aspects relating to property. Follow Catherine on Twitter or via her Blog.