By – Catherine Cashmore

“The home, built in 1857, had been unoccupied for years” said the report of a dilapidated Victorian-era mansion in Sydney’s Balmain East.

Situated in an exclusive residential pocket next door to Balmain East ferry wharf and sporting bayside views of Sydney’s Harbour Bridge, the 457 square metre block of land attracted 200 people to the auction, 18 registrations to bid, and sold $830,000 above the reserve to a local home buyer for $2.68 million.

According to Property Observer, the site had been acquired in 1973 for $33,500 by the notable gay right’s activist and historian, Alexander ‘Lex’ Watson – president of The Pride History Group, and lecturer in Australian Politics at Sydney University, who sadly passed away earlier this year after a long battle with Cancer.

$33,500 in 1973 dollars would be $289,724 in real terms today – making the selling price of $2.68 million, a value almost ten times as great.

The location was the key of course, with planned upgrades to Balmain East ferry wharf, which will now receive services from the Parramatta River along with extra ferries to McMahons and Milsons Point, further enhancing its value.

Had the home been only a few kilometres away, a few hundred thousand could have been wiped off the price tag and the media sensation may not have been so great, even so, it is not the only dilapidated property to make the press of late.

Opportunistic buyers caught up in Sydney and Melbourne’s property boom, have snapped up a string of empty homes, selling under stiff competition while exceeding all expectations of price.

An empty hat factory on Wilson Street, Newtown, also vacant for years, sold earlier this month for $1.725 million.

A dilapidated home on 360 square metres of land in Thornley St, Leichhardt, vacant for more than 30 years, sold a few weeks ago for $1.4 million at auction.

A home in total disrepair at 19 Durham St, Stanmore, situated on 172 square metres of land, vacant for years and sold for $923,000.

And not to leave Melbourne out, an unliveable Richmond property on 726 square metres of land, also vacant for years, sold for $2.544 million – $900,000 above the price it achieved only two years ago.

Barring the last example that came with plans and permits for two town houses, these properties transacted for nothing more than their land value. However, while the buyers purchased a location, they did not pay for the services that rendered that location valuable or, in the case of the first example, compensate the local residents for suppressing access to some of the best views in town.

Instead, reinforced by inelastic zoning constraints, generous tax treatment, and unrestrained speculative growth in dwelling finance commitments, they unwittingly rewarded the sellers with a substantial unearned gain for withholding valuable land from use and depleting the nation’s housing supply.

This means of ‘creating wealth’ common in most western nations, sits at the root of many of our economic and social problems today. It has both a debilitating and destabilising effect on the economy, evidenced clearly in a painful and rising trend of income and housing inequality that burdens the capacity of the ‘welfare state’ to compensate.

Interestingly, Lex Watson, the prior owner of the Balmain East property cited above, was purportedly greatly influenced by the writings of John Stewart Mill whose work was said to be: “the touchstone of his life and later activism.”

Born in London in 1806, John Stewart Mill is remembered as: “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century.”

Inspired by his father James Mill, who tutored his nine children with daily lessons in Latin, Greek, French, history, philosophy, and politics, John Stewart Mill was a leading economist – a prolific logician, who dedicated his life to championing the causes of liberty and equality, while advocating ‘radical’ ideas, such as the abolishment of slavery and equal rights for women.

In 1848 he published the most prominent textbook on economics in the 19th century: Principles of Political Economy – critiquing systems such as communism and socialism and cementing Mill’s reputation as a leading public intellectual.

Extending on the ideas set out by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Mill employed concepts that that have been written out of today’s economic narrative, that conflate land and capital – virtual opposites – while failing to distinguish between income that is ‘earned’ and the economic surplus that disproportionately flows to those that “love to reap where they never sowed.” A process best set out in Mason Gaffney’s book, “The Corruption of Economics.”

Writing on the moralities of taxation in Book V, Chapter II of ‘Principles of a Political Economy’ Mill commented:

“The ordinary progress of a society, which increases in wealth, is at all times tending to augment the incomes of landlords; to give them both a greater amount and a greater proportion of the wealth of the community, independently of any trouble or outlay incurred by themselves. They grow richer, as it were in their sleep, without working, risking, or economizing.”

From this Mill concluded that the government should collect society’s economic rents in lieu of taxes that impede productive labour and industry, including taxes on the improvement and the transfer of property, (stamp duty) which he said, should rather be: “distributed over the land generally, in the form of a land-tax.”

He was not the first or last to do so.

He followed a long line of influential activists, from Thomas Paine, who in his 1797 publication Agrarian Justice stressed:

“Men did not make the earth…. It is the value of the improvement only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property…. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land, which he holds.”

To most recently, Dr Ken Henry, who chaired Australia’s ‘Future Tax System Review’ and noted: “… economic growth would be higher if governments raised more revenue from land and less revenue from other tax bases.”

The classical economists recognised that unless profits from the ‘enclosure of the commons’ – land, water rights, minerals, and so forth – were effectively collected and shared for the benefit of the community, all productive gains, every improvement in society and the economy, would be capitalised into rising locational land values, enriching those that owned the assets but more so, those who created the credit and traded on the debt.

This is equally applicable to reductions in the cost of construction.

For example, news that high-density apartment towers close to public transport in Sydney, will no longer require parking facilities, delivering an estimated saving of $50,000 – $70,000 in development costs, will do little to ease affordability. Rather it will simply leave more funds available to bid up the price of land and this is precisely what we are seeing in Australia – sky rocketing land prices requiring ‘super tall’ structures to provide a viable return on investment.

While the small one and two bedroom units may be spruiked as affordable, when calculated by cost or rental value per square metre of floor space, they are remarkably expensive.

Mason Gaffney expanded on the theory, coining the acronym ATCOR – “All Taxes Come Out of Rent.” Showing that whether renting or buying, total tax liabilities from whatever area carried by the consumer, deduct from the cost of a site to the extent they limit the amount a buyer is both prepared and able to pay.

It follows that the removal of all taxes would naturally wash up into higher prices for real estate, which in theory leaves the resulting rise in the economic rent of land ‘just’ enough to replace the forgone revenue. (For more, see Fitzgerald (2013) “Resource Rents Of Australia”)

When that liability falls on productive industry, deadweight losses occur. For example, 90% of our taxes are distortionary, adding 23% to prices of goods and services.

However, when the burden falls on land and monopoly rents – minerals, fuels, the broadcasting and communications spectrum, patents etc. The reverse is the case.

In respect of land, a higher tax rate levied on the unimproved value would discourage leaving dilapidated homes vacant for years while we struggle with an assumed housing shortage – suppressing the speculative element that adds to the volatility of the market cycle.

Furthermore, when the gain is collected and used to fund the expansion of infrastructure in order to service a growing population, the tax base is expanded without a subsequent lift in rates.

In the 19th century, nature’s ‘free lunch’ was largely limited to the aristocracy of the great landed estates, today monopoly profits are absorbed by the financial sector which wields significant political leverage from lending ‘endogenously’ created credit against real estate collateral, with the compounding interest disproportionately increasing levels of household debt. As I pointed out previously – Australia will increasingly feel the effect of this as we move into 2019.

Our current tax system is crooked. It allows large companies to jump through loop holes in legislation and ‘cook the books,’ shipping profits offshore, leading to an estimated $1.6 billion in tax revenue forgone, while land on the other hand, is used by investors as an effective tax haven.

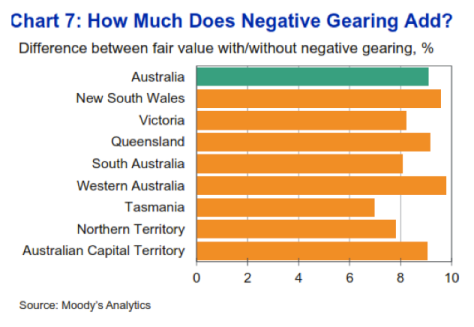

In a recent post by Dr Gavin R. Putland of the Land Values Research Group, he notes:

“No matter how high your gross income may be, you can make your taxable income as low as you like, simply by buying enough negatively-geared properties. Such artificially reduced taxable incomes are used in ATO statistics on negative gearing, which are then trotted out by the property lobby as “proof” that most negative gearers aren’t rich — as exposed, for example, in Michael Janda’s article “The myth of ‘mum and dad’ property investors” (The Drum, 24 September 2014).”

Enlightening the disparity of our tax laws further, Putland includes a citation to a series of exchanges posted in the comments section of Michael Janda’s article in The Drum:

“AE:

… Deductions for expenses incurred are a fundamental of our and every other economy. Show me one society where you cannot deduct expenses incurred.

Gavin R. Putland:

How about *our* society? The cost of commuting to work is manifestly a cost incurred for the purpose of earning your wage or salary, but you can’t deduct it against your wage or salary (or anything else) for tax purposes. QED.

Mitor the Bold:

That’s an ATO commandment, but theoretically you should be able to.

Overit:

Actually, Mitor, it predates the ATO by about 200 years, and is derived from a pre-industrial-revolution House of Lords ruling which said that if tradespeople choose not to live in or over their business premises, then they should not be able to deduct the cost of travelling to their work.

However, I agree that theoretically you should be able to. Which is why the novated vehicle lease business has grown so rapidly, because that effectively enables people to deduct the cost of travelling to their chosen place of work. Bad luck for all of us who travel by public transport.

JoeBloggs:

The cost of travelling from your home to work is not a work related cost. It is the cost relating to your choice where you live, a personal aspect of your life. No worker, contractor or business can claim as a deduction ‘personal’ costs. QED.”

As Putland points out:

“So there you have it, proles: The industrial revolution never happened. You always have the option of living at your place of work. If your place of residence is somewhere else, that is a “personal” choice on your part, and the cost of travel between the two is a ”personal” expense, not a work-related expense. If you want a big deduction against the wages of your labour, you’ll have to gear up and speculate on assets.”

Australia’s economic narrative is more concerned with suppressing wages than high land values.

Joe Hockey has unashamedly stated that any rise to the minimum wage “will cost jobs” and “reduce competition,” while remaining notably silent on the average CEO pay, which sits at an estimated 63 times average earnings (as at 2013,) as well as showing scant regard for rising land values which increase the associated costs of running a business, while discouraging growth in productive industry.

It uncovers a damaging Neo-Liberal agenda, which will do nothing to raise the living standards of Australians struggling to make ends meet.

Meanwhile in Germany, the house price-to-income ratio has fallen by almost a third nationally since the early 1990s, yet residents enjoy low unemployment and some of the highest wages per capita in the world – including the highest minimum wage in the world. Germany weathered the 2008 depression better than any other country in Europe by maintaining its focus on value adding growth.

(The Economist – German house price to average income.)

The public needs to recapture the debate and push for a better set of democratic tools, that let the people decide directly on the benefits that can aid their communities, rather than the current state of affairs which is coloured with vested interest, polarising voters with false promises and flawed economic thinking.

The rise of citizen’s juries, where a diverse and representative group of people are randomly selected and given the information and training needed to deliberate together on matters of policy – for the benefit of all, not just a few – limiting the power of corrupt government officials, may take us one step closer to achieving this.

Top of the agenda should be every citizen’s right to affordable access to land and shelter.