The fact that Australia has an affordability crisis is not in dispute. Rather, government inaction for more than a decade must be questioned.

Since the early 2000s, there have been three Senate Inquiries to tackle Australia’s escalating land values and declining rates of homeownership, including Australia’s Future Tax System Review that made a number of recommendations on housing reform.

The first inquiry conducted by the Productivity Commission in 2004, determined that prices had surpassed levels explicable by demographic factors and supply constraints alone. They stressed that a large surge in demand had rather been “predicated on unrealistic expectations (in a ‘supportive’ tax environment) of on going capital gains.”

The second inquiry overseen by a Select Senate Committee in 2008, found that the average house price in capital cities had climbed to over seven years of average earnings and once again, they identified inequitable disparities in the overall fairness of the tax system, that had lead to “speculative investment on second and third properties.”

Australia’s Future Tax System’ review conducted in May 2010, stated that tax benefits and exemptions had been capitalised into higher land values, encouraging investors to chase ‘large’ capital gains over rental income and landowners to withhold supply.

The third and last inquiry which is currently being conducted by the Senate Economics References Committee commencing in March 2014, received a key submission from Prosper Australia examining nine chief economic measures of land, debt, and finance – and found all to be at, or close to historic highs.

“It took forty years from 1950 to 1990 for housing prices to double, but only fifteen years between 1996 and 2010 to double again.” (Soos, Egan 2014).

The submission demonstrated a sharp rise in the nominal house price to inflation, rent and income ratios, driven by a rapid and unsustainable acceleration of mortgage-debt relative to GDP.

The current trend dwarfs the recessionary land bubbles of the 1830s, 1880s, 1920s, mid-1970s and late 1980s that triggered economic havoc, leading Australian households to suffer some of the highest levels of private debt in the developed world.

Today, the investor share of the market is close to 50 per cent. Investor finance commitments are rising at their fastest pace since 2007. Sixty-five per cent of loans to investors are on interest only terms and 95 per cent of all bank lending is being channelled into real estate – mostly residential.

Yet despite these findings, policy makers and industry advocates repeatedly claim that the primary driver of Australia’s affordability crisis is a lack of supply – and that increasing the stock of housing alone, will reduce prices enough to rectify the problem without the need to address the demand side of the equation through necessary and far-reaching tax reform.

Ultimately, this is not possible because our policies work directly against it.

Investor and housing tax exemptions worth an estimated $36 billion a year, have distorted the Australian dream of owning a home into a vehicle for financial speculation.

Consequently, rising land values that impoverish the most vulnerable sectors of our community are widely celebrated – while Australia’s federal members of parliament in possession of a $300 million personal portfolio of residential dwellings, stand solidly against all recommendations from previous Senate Inquiries for meaningful and equitable tax reform.

“The trends in the data suggest a sizeable majority of federal politicians have a vested interest in maintaining high housing prices, particularly since most have mortgages over their own investments.” (Egan, Soos and David)

Under current tax policy, investors that withhold primary land and dilapidated housing out of use are rewarded with substantial unearned incomes due to government failure to collect the economic land rent (the ‘capital gains’) society generates through public investment into social services.

The subsequent uplift in values that comes as the result of neighbourhood upgrades and taxpayer funded facilities – further accelerated by plentiful mortgage debt and restrictive zoning constraints, capitalises into the upfront cost of land by tens of thousands of dollars year on year. Yet rental incomes, at typically no more than $18,000 to $19,000 per annum are a mere trifle in comparison.

In the 12 months to September 2014 alone, Melbourne’s median house price increased by 11.7 per cent – over $60,000. In contrast, gross rental yields at 3.3 per cent are currently the lowest in the country and the lowest on record.

This broadening divergence between rental income and ‘capital growth’ typifies the commodification of housing used only as a tool for profit-seeking gain.

Indeed, net rental incomes in Australia have been declining since 2001. Growth in both the relative and absolute number of negatively-geared investors between 1994 and 2012 has soared by 153 per cent. In contrast, positively-geared investors have increased by a much lesser 31 per cent.12

Large divergences between rental income and land price inflation thus produce an unhealthy challenge to both housing affordability and economic stability.

They lead to ‘speculative vacancies’ (SVs) – properties that are denied to thousands of tenants and potential owner-occupiers, lowering relative vacancy rates and placing upwards pressure on both rents and prices. The housing supply crisis is therefore greatly obscured by current vacancy measures that cannot identify sites that are withheld from the market for rent-seeking purposes.

The consequential subversion of housing policy is evident when it is considered that since 1996 Australia has built on average one new dwelling for every two new net persons nation wide. Yet over the same period, government legislation, politically manufactured to protect the unearned profits of a large cohort of speculative investors, has resulted in vacant median land prices on the fringes of Australia’s capital cities ballooning from approximately $90 per square metre in 1996, to over $530 per square metre today.

Indeed, there is no better example of the astonishing escalation of land price inflation than the very recent report of a Melbourne family who purchased a 108 hectare Sunbury ‘hobby farm’ in 1982 for $300,000 and following new residential rezoning, have realised an estimated windfall gain of over $60 million.

This means of ‘creating wealth’ common in most western nations sits at the root of many of our current economic and social problems. Our tax and housing policies shift income to landowners, eroding the living standards of future generations of Australians who are required to shoulder an increasing burden of debt just to secure a foothold on the fabled ‘property ladder’.

The effect is to broaden the intergenerational divide as families are forced to live on the threshold, marginalised into areas lacking essential amenities and jobs, while 92 per cent of speculative investment into real estate pursues the ‘capital gains’ associated with second-hand dwellings, rather than increasing the stock of housing through the purchase of new supply.

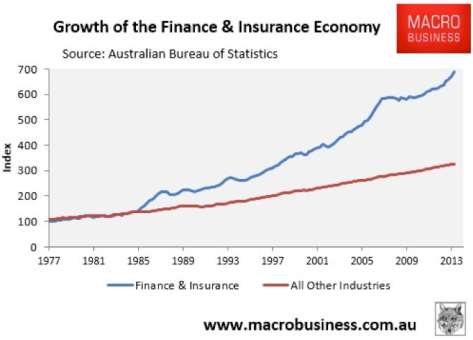

Aided by a complicit banking system, Australia’s rising house prices produce wide ranging inefficiencies to the economy. High land prices damage Australia’s competitiveness with higher living costs. The resulting demand on both business and wages channels investment away from genuine value adding activities, leading to a gross and wasteful misallocation of credit to feed an elevated level of speculative rent-seeking demand.

The debilitating and destabilising effect on the economy can be evidenced clearly in a painful and rising trend of income and housing inequality that places an unsustainable strain on the capacity of the welfare state to compensate.

Australian’s like to think of themselves as a ‘fair go’ society –however, inequitable disparities in our housing, tax and supply policies result in an English-style class divide, evidenced in:

- Fewer Australians owning their homes outright [i]

- A rising percentage of long-term tenants renting for a period of 10 years or more[ii]

- A decrease in the number of low income buyers obtaining ownership, particularly families with children [iii]

- A drop in the number of affordable rental dwellings with a marked increase in the number of households in rental stress[iv]

- Greater requirements for public housing.[v]

- A rise in homeless percentages and those who drift in and out of secure rental accommodation –with ongoing intergenerational effects[vi]

- An increase in the number of residents living in severely crowded accommodation.[vii]

As many as 105,000 Australians are currently homeless, while between the dates of 1991 and 2011 homeownership among 25-34 year olds has declined from 56 per cent to 47 per cent, among 35-44 year olds from 75 per cent to 64 per cent, and among 45-54 year olds from 81 per cent to 73 per cent.

Homelessness is often blamed on dysfunctional relationships, mental illness, drug abuse, domestic violence, job losses and so forth. But at the root lays an acute lack of affordable accommodation available for the most impoverished members of our community in need of both security and shelter.

‘Speculative Vacancies 7’ gives a unique insight into the impact of current housing policy by highlighting the total number of underutilised and empty residential and commercial properties currently withheld from market.

Melbourne is a perfect case study for this report.

• Its real estate is ranked among the most expensive in the developed world

• It has dominated Australia’s population growth, attracting the largest proportion of overseas immigrants, alongside strong immigration from interstate.

As government and the real estate industry are not sources of impartial information, the report adds a valuable dimension to understanding the divergence between real estate industry short-term vacancy rates (the percentage of properties available for rent as a proportion of the total rental stock) and the number of potentially vacant properties exacerbating Australia’s housing crisis.

Download Speculative Vacancies 7.

Related media:

- ABC online: Water Use study finds vacant flats in Melbourne’s Docklands

- Herald-Sun: Foreign Buyers Behind Docklands Hidden Vacancies

- Macrobusiness on Melbourne Ghost City Revealed

- The Age – The Age: Ghost Tower Warning for Docklands

- Business Spectator – Australia’s housing policy is a total con job

- ABC News24 – ABC News 24 -with Tony Eastley

(Footnotes)

[i]ABS – In 1996/7, 42% of households owned their home without a mortgage. This proportion is now down to 31%

[ii]ABS -A third of all private renters are long-term renters (defined as renting for periods of 10 years or more continuously), an increase from just over a quarter in 1994

[iii]ABS – A drop of 49% to 33% between 1982 and 2008

[iv]ABS – In 2009–10, 60% of lower-income rental households in Australia were in rental stress.

[v]AHURI 2013 – 28% increased demand for public housing projected by 2023

[vi]ABS – Between 2006 and 2011 the rate of homelessness increased by 8% from 89,728 to 105,237

[vii]ABS – The total number of people living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings jumped 31% (or 9,839 people) to 41,370 from 2006 – 2011